Montserrat Andrée Carty: I thought we might start with talking a bit about your recent memoir called, Story of a Poem. It’s a book of prose about the revision of poetry, but it's also about the revision of self. I think it's really wonderful how you take us through the whole process, like, "This is how my poem changed," and “this is how I changed.”

Matthew Zapruder: Yes. In Fall 2018, it was a very difficult time nationally, and in California, in particular, because it was the first really terrible fire season that we'd had. That was the year of the Paradise fire that killed nine people, I think. Just a very scary, destabilizing time. Also, in my personal life, as a parent, we’d recently moved houses, and it just was a very strange, upsetting, difficult time. I had the sense that maybe writing my way through that time would somehow help.

I went into the idea that I would write every day, and in correspondence with a friend of mine, Catherine Barnett, who is a wonderful poet, and we would write 500 words a day, minimum, and we'd just send them to each other each day. We could write about whatever we wanted, about poetry, about what we were reading, about something else. I also had this other idea, which was that I would start a poem, and then write about the revising of it, write about the writing of it and see what happened, try to engage in this practice that I called slow poetry. Which was just really slowing myself down, and observing what I was doing, writing about it, and writing through it.

Those were my two very vague ideas about this project, both process-based. I didn't know what I was going to write about. I didn't know what direction things would go in. I just engaged in that process, starting right at the beginning of November 2018. It went on for about five months, I think, of writing. Then I was left with this giant pile of words that I had written about all sorts of different things to go through and sort through and figure out how to turn into a readable arc of something.

I'm so interested in process. I love reading about anybody's process and how they make things and how they do things. It almost doesn't matter what they're making. I just love it. I also love reading about it. I had in my mind, maybe I could write a book that revealed the process of writing a poem to myself and hopefully to readers.

MAC: I love process as well. In the memoir, you write about the ways that a poem can evolve on a granular level. You share the very first draft of a poem. Then at the end, it's completely transformed. You can see the spirit of it in there, but it's so different. I think that's so often how it is in most art making. We take little fragments or pieces of something and then get curious about it, and it evolves.

I love seeing echoes of Story of a Poem in your new book of poems, I Love Hearing Your Dreams. We read about the phrase “two sleeps” in Story of a Poem and then see that as the title of a poem in I Love Hearing Your Dreams. Like you, I love thinking about process and how nothing we do is wasted. We can spend so much time on a piece of art–– let's say it's a poem, or an essay, or a book, or a painting, or whatever it is––and then be like, "Oh, this isn't working," for whatever reason. Initially we can feel like, "Oh, this is a waste," or, "I wasted my time." It's so not a waste. I have found that it's always leading you to the next thing.

MZ: Yes, it's funny to hear you say that about wasting time because I was thinking, one of the animating spirits of this book was that famous line by Rilke, at the end of Archaic Torso of Apollo, in translation, “You must change your life.” I was thinking that was the animating spirit behind beginning. Maybe it would have been better to say “you must revise your life.” You must change your life and to trace the process of changing it and to be as attentive as possible to that changing of life and changing of attitude was one of the guiding spiritual principles. I also think about, when you say waste, about that very funny and tragic ending of the James Wright poem, Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy's Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota. The end of the poem is, "I have wasted my life." That's the last line of the poem. I think about that. Of course, you probably think of that ordinarily as being a negative thing, "I've wasted my life," but maybe in a way it's a badge of honor. "I've wasted my life in the sense that I've been willing to try anything, and I've been willing to experiment and explore."

As you said, nothing is wasted. Everything is useful. We’re talking about this in the aftermath of the presidential election. I think about, "What can we do with the aftermath of this? What can we do with this and not treat it as a wasted opportunity or wasted time?" I don't know. I have absolutely zero answers to that. I may have some beginning thoughts. I think that it's just a mentality of we learn from everything, we move forward from everything. That's the good and the bad.

MAC: That's right.

MZ: Not to minimize anything, but just to say that that's just how life is. You have to pick yourself up and move on. Changing things and wasting things were definitely on my mind as I wrote that memoir.

MAC: You’ve said, when something doesn't feel right in the first few drafts, you put it away. Then, maybe you find a new image or a new line that comes to you and then it unlocks something. In this collection, I Love Hearing Your Dreams, is there a poem in particular where it wasn't quite right and then you just said, "I'm going to forget about this for now," and then something happened that opened it back up? I'm sure it happened to more than one poem, but is there one that sticks out in your mind?

MZ: Oh, that's a great question. At the beginning of Story of a Poem, I sit down to try to write a poem, and I think about this phrase “two sleeps” which is talking about time in terms of sleeps, which is a common parlance among parents. It's like, "When's Thanksgiving?” “It's three sleeps from now." Because that's something that kids can get their head around. I remember the first time I heard that, it was confusing to me. It was just a weird and beautiful phrase. I began the poem and Story of a Poem with that two sleeps idea because it made me think of my wife and my son who were sleeping and their two sleeps. I started the poem with that, but at some point in the drafting process, that phrase dropped out of the poem. It wasn't about that anymore.

It became about other things, or it moved into a different center of gravity, which happens all the time, as you say, in all forms of art. You start with a seed idea. Sometimes that idea or that phrase or that color or that line that you drew, whatever, stays the whole time. That can happen. A lot of the time it doesn't. The flexibility of being able to let things go, of course, is important in art as it is in life.

I'm fortunate enough to be friends with a poet, Mary Ruefle. She's one of our great American poets. I sent her Story of a Poem when I was done, and I mentioned her a few times in the book as well. She wrote me back a really lovely note, but she said, "The only thing I was disappointed in with the book was that you wrote this poem in which you had this phrase, ‘two sleeps.’ I was really sad that it wasn't in the final draft." I thought, "Maybe I'll write her a poem." It's called Two Sleeps. That's why that poem is in there. Because it's a response to a comment that she had. That's a poem that hung around for a long time.

There's lots of poems that I tried many, many times and I would get frustrated and bump up against in the book. I just wasn't ready to write them yet. Some came pretty easily, pretty quickly, but a lot of them didn't. That's pretty common for me. I don't know if you could tell the difference from reading them between one or the other, but some of them, I look at them, and I'm like, "This was a labor that took months, and every line was just excruciating."

MAC: It's so funny with poetry because some people might think, "Oh, it's just a couple of lines. How hard can it be?” It can take a decade to figure out those lines!

MZ: Why do you suppose it takes so long sometimes?

MAC: Well, I was thinking about something you said in your book about building a structure around what you love. That's really what I come to poetry for, both writing and reading it. That's what's so powerful about it, is that you find this line or an image that you love, and you need to build around that so that what you're feeling can then translate for the reader, and they can get it, too. It’s the building around it I find is what's really hard, or can be.

In hearing you talk about Two Sleeps, I am thinking about the different ways that we can read a poem and have these different interpretations, and it leaves room for interpretations, maybe more so than the essay or fiction or other kinds of writing, and how that can be so magical, and also makes it more challenging maybe.

MZ: Yes, totally. I think that one of the things I wanted to do when I wrote Story of a Poem, was to maybe help readers, because I think that sometimes when you read a poem, and I'm guilty of this, too, it feels like words of wisdom, or some statement. Poems can carry this authority basically inherent in, I think, the genre. We go to poetry and we just think, "Oh, it's a poem. Every word was carved out of granite to find the truth," or something. Seeing how a poet gropes their way towards meaning and how that meaning changes as they live their lives, and they learn from the poem and the poem learns from their lives, and that revising, I think is also helpful for thinking of the poem as more like a living document of consciousness. It's a record of an interaction, with the world and with their own mind and with other people, at a certain moment in time.

I think that one of the things that's hard about reading poems sometimes is that you read them and you expect them to be definitive. Because we've just been taught to think that way about poetry. That's really not how most poems are. They're tentative. They're attempts. They're noble and charming and well-meant attempts at grasping something that can never probably be fully grasped. To show the process of trying to make one, I also hope that could open up a reader's approach to a poem a bit as well.

MAC: I love that. I want to circle back to something you just said about a moment in time. In another interview you talked about having a poem that was published in The New Yorker that was deeply personal, that was just a moment in time. And also, sometimes reading a book back, you feel like, "Oh, I'm actually a little more of a different person now." That's so natural because we're all evolving constantly, and I'm thinking about this all the time in terms of art making and putting things out into the world. It can be a bit difficult, I think, as an artist to see previous versions of yourself out there, and you can't be like, "Oh, wait, I changed my mind about that thing. I learned something different." You can't go back and necessarily do that, other than making new art and putting that out. How do you make peace with that as an artist?

MZ: I don't feel peaceful about it at all. I think that a lot of time, a poem is a record of a moment of consciousness. It takes on a universality because we're all human beings, and we experience a lot of the same things. We don't experience them in exactly the same way, of course. We go through things, and those things are familiar to each other. When someone is having a particular experience on, like October 12th, 2022, that's going to resonate with somebody, 1 or 2 or 20 or 50 years or 100 or even 1,000 years later, who knows? The person who felt that way at that moment when they wrote the poem has probably moved on to different things. Literature, hopefully, has an eternality to it, but the person isn't feeling that way all the time or even necessarily five minutes later. That's okay. That's just the nature of the game. When it comes to writing about other people, or your personal life, which is for a long time, not something I particularly did, I became painfully aware of the consequence of freezing, not so much my kid who I write about, who is neurodiverse, but my experience of dealing with his difference and coming to understand it and love it and appreciate it has been a long journey that continues. But there have been many, many moments where I struggled, or I was trying to understand something or come to terms with something hard and that continue to be hard. The record of those moments in poetry or in any writing is something that people can understand and relate to, but they don't fully characterize by any means, my attitude towards my child or my life or whatever.

Part of writing prose about writing was also an effort to give more dimensions to those feelings, which is harder to do in a poem. It's not impossible, but it's difficult just because the real estate is so much more limited in a poem.

It's more like this bolt from a single moment of consciousness, which can paradoxically have this eternality to it or resonance throughout time. Whereas prose, you can stop and talk about the different aspects of things and approach it from 10 different ways with 20 pages to do it.

MAC: I wanted to ask you about literary friendship, because that seems so prominent in your life. You talked about exchanging work with Catherine Barnett and Ada Limón. This exchange seems to be very important to you. It's important to me, too, to be able to be in conversation with other artists, other poets.

I know you were saying in an interview, too, about how with some of these poets, at least at the beginning, maybe you didn't know them deeply on a personal level, but you knew them deeply because of their poetry.

MZ: I'm not a particularly gregarious or social person. I can rise to the occasion, but I'm actually not the most socially comfortable person. I don't make friends super easily. I'm not somebody who is constantly palling around. The closest, long-term, most meaningful friendships and relationships I've had, both with peers and with people older than me, and frankly, with the dead–– people who I never met, whose books I've only read, have come to me through poetry. Some of my longest running friendships I have with Matthew Rohrer and Joshua Beckman, who are, I think, some of the greatest poets writing alive today. I met them in the late '90s and in different ways.

Those friendships, which have also in some ways been professional relationships––I edit Matt's books for Wave Books, and I work at Wave Books with Joshua Beckman–– and also have been his editor on many projects, too. Those friendships, those connections, they've been some of the greatest gifts to me in my life. You mentioned Ada Limón. She's somebody who I only know through poetry, and we're very close. I have immense respect for her, and I adore her, and she's a great, true friend.

Victoria Chang is somebody I've gotten to know over the years, and she's an amazing person and one of my favorite poets, and she has an incredible new book out, With My Back to the World. I think it's just about the best book that I've read this year. I can mention lots of other people, too. How fortunate I am, and of course, I met my wife through poetry. She was studying fiction, but we met at a summer program at Amherst.

Poetry has brought me everything, basically, that's good in my life, just about, other than my family of origin (my brother and sister, and mother, and late father). Those personal relationships to me are inextricable from the practice. A lot of time when I want to write a poem, I often think of my friends who are poets, or I think about poets whose work I love, and then I'm responding to them or interacting with them. Just as meaningful to me as responding to an event or something that happened to me, or some image that comes to mind, is to think about a person.

A lot of time those people are poets. When I'm lying awake at 3:00 in the morning counting my blessings, one of the many blessings I count is these friendships that poetry has brought to me. I don't know who to thank for it. Whoever it is, thank you.

MAC: That's beautiful. I also just want to give a little shout out to Wave Books, which is an incredible press.

Toward the end of Story of a Poem, you have a line, "I write so I can keep dreaming a little while I'm awake." After reading that, I was thinking about the parallels between dreams and poetry, how we write in fragments, the line here and there, and then we dream in fragments as well.

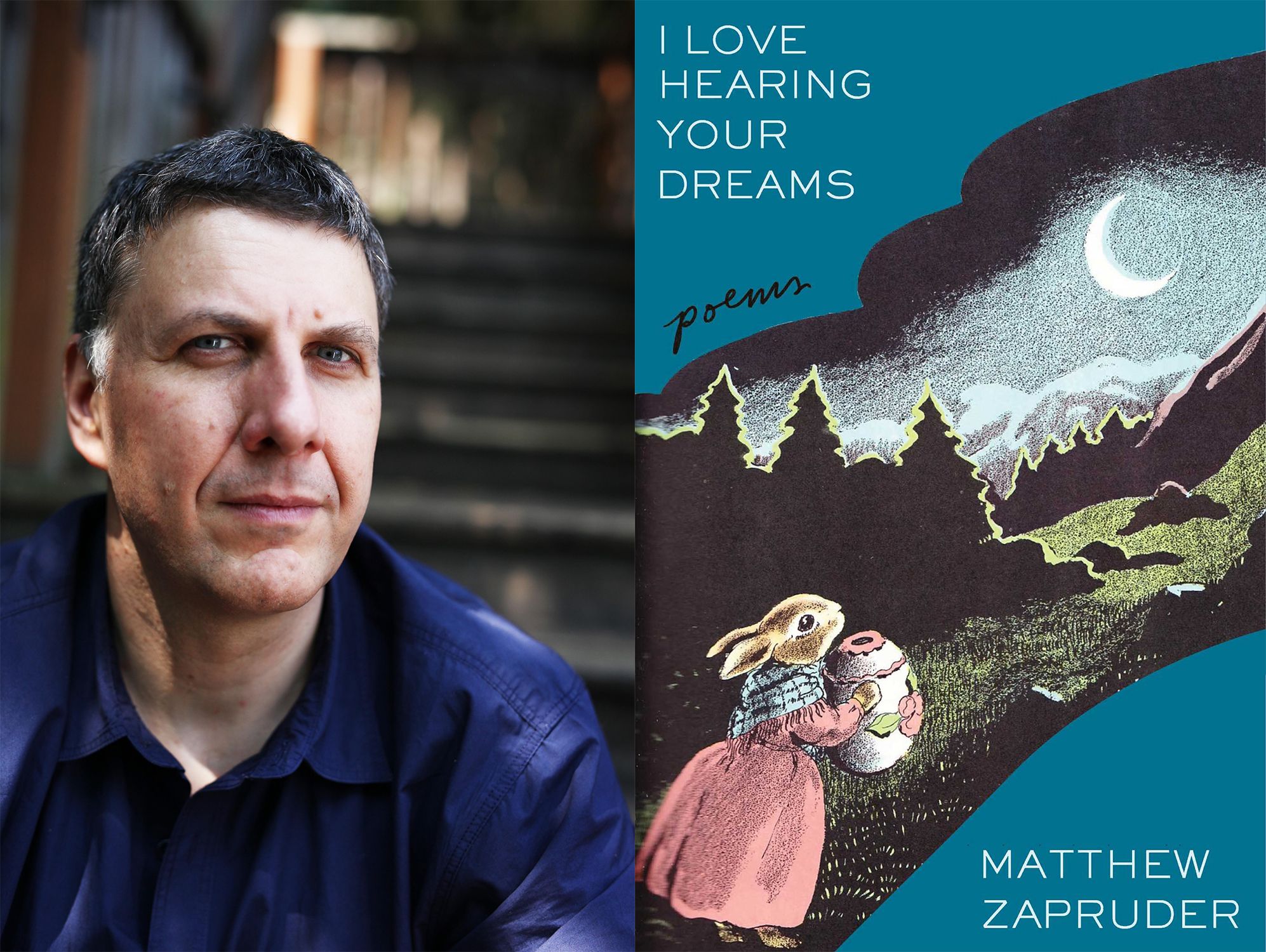

I also just want to say how much I love the cover of this book, I Love Hearing Your Dreams.

Matthew: Thank you. It's a part of a page in a children's book that's called The Country Bunny and the Little Gold Shoes, which is an early 20th century children's book that I actually was not familiar with. I was talking with my friend, Daniel Handler and said "I don't know what the cover of my book should be." He just sent me this picture, and he was like, "This is what it should be." And I said: "You are totally right." Daniel has an incredible aesthetic sense and just great taste and is tuned in. I sent it to my publisher and they got permission.

It's a bunny holding a big egg, but it almost looks like an urn. She's getting ready to go up a giant side of a mountain and she's facing the crescent moon, and she's clearly at the beginning of a big journey or at least in the middle of one. She's carrying something that needs to be carried there, but we don't know what's inside. A lot of people know that book from their childhood. I didn't happen to know it, but a lot of people recognize it.

MAC: It was like one of those things where you see it, and you're like, "Oh, this is familiar," but you didn’t know exactly where from.

MZ: Yes. I think it looks familiar even if you've never seen. It looked familiar to me, too. I'd never seen it. That's the thing, to be honest, I really loved the most about it is that it has the symbolic quality, the quality of symbol without being overly tethered to a particular meaning. It means something, and you can think about it, and you can say what it means to you. It has a definitive direction of meaning and suggest things and demands to be understood in certain ways, but it's not translatable one-to-one like, "This stands in for this, this stands in for that." It's perfectly how poems should operate, in my opinion.

MAC: I love the collaborative process of that, too. Somebody showed it to you and you're like, "Yes, that's right."

MZ: Yes. That way, too, it was perfect because so much of this book mentions friendships, and it’s poems for people, it's poems for other poets. There are a couple poems in there for my friend, Dean Young, who passed away. There's lots of poems like that. In a way, you're right. I hadn't thought of that, but that's another thing that is probably perfect for this book about it, yes.