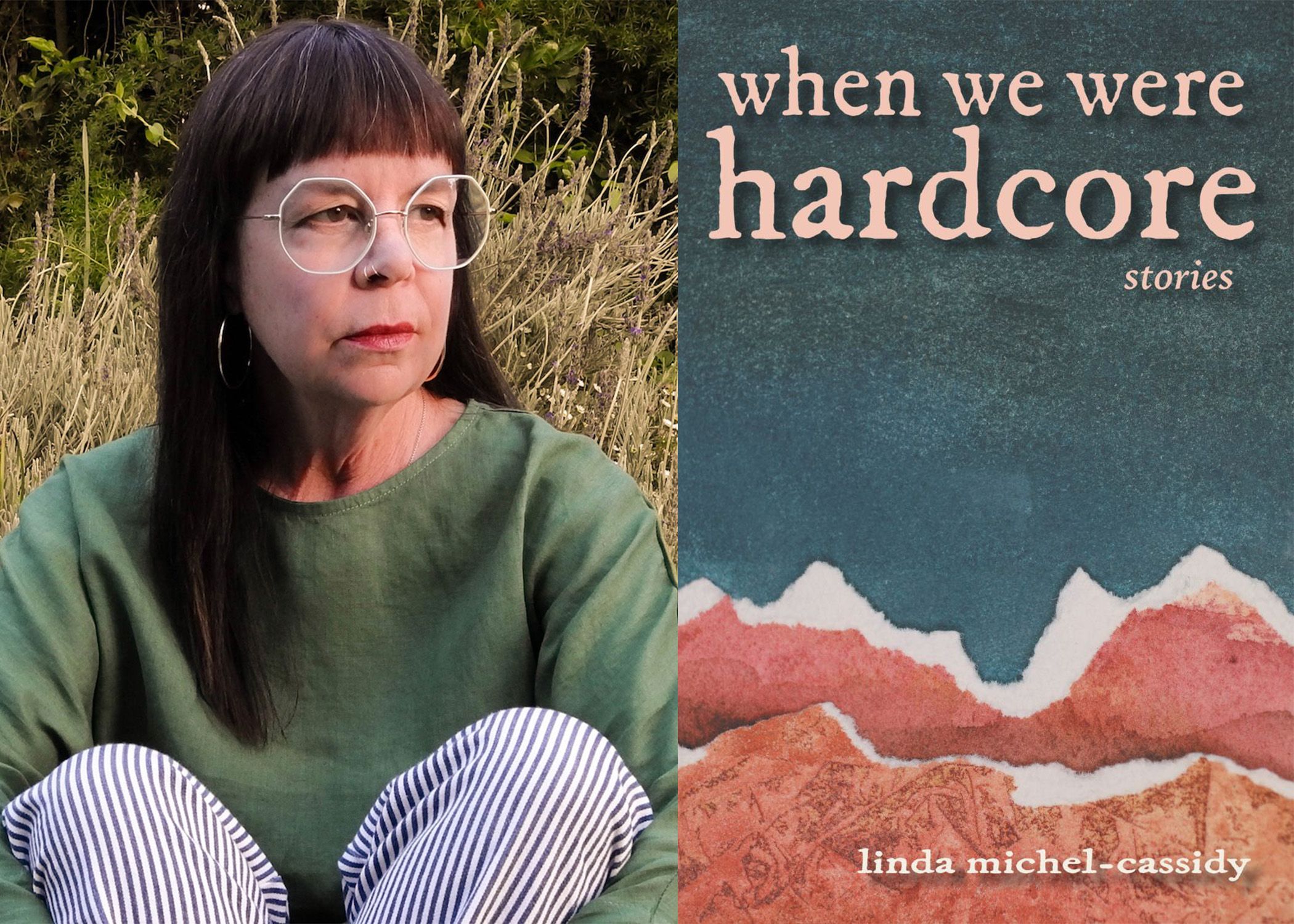

Photo Credit © Jia Oak Baker

Allison Wyss: Let’s start with death—I like to be grim! The early stories circle death in fascinating ways, often situated in the aftermath or when it is looming.

Linda Michel-Cassidy: I’m interested in the unknown and death is a subset of that. People going missing, the inner workings of our bodies, the subconscious, lost memories, all if it. Death being the biggest question. But since I’m an avoider, I try to go at things obliquely. I think death is the subtext of our lives. I don’t mean that in a sad or morbid way, but life is finite, whether we like it or not. I don’t constantly think about it, but it is the quintessential understory, right? We’re living in a timeline, but we can only know part of it.

I feel the rural areas I write about deal with death as a phase as opposed to an ending, which seems more balanced. Useful, even. There were seasons with so much loss that this mode of acceptance might be the only way to avoid being continually enveloped in sorrow.

AW: You say the balance is useful—I agree. It’s not merely a fact of life, but death has a function in your stories.

LMC: It’s the ultimate “who knows?” situation. It's a topic that rests within every story ever told, whether it’s named or not. Each of us live our own specific and, relative to time, small life, and we want to leave a mark. There is a big disconnect with visitors to the beautiful regions I write about, absolutely stunning in all seasons and the facts of the day-to-day. What makes a sparsely settled mountainous place feel like magic factors into what makes living there feel tenuous.

Perhaps death expands to encompass all the things we cannot know, but also loss. Death is concrete; we know when it occurs, but other losses have this creeping drawn-out effect and the borders are less clear. I think that fuzziness can extend the pain, maybe even allow it to be never-ending.

AW: Your idea of death’s fuzziness actually makes me think of the undead. We don’t get zombies or vampires in this book, but we do get taxidermy. We get characters who are close to death but not quite there, or it’s unconfirmed. The narrator is both centered and missing in “As Happy as I Could Remember”—sort of undead. The taxidermied animals are killed a second time in “A Pile of Stuffed Animals.” And “Tumbled” is not about death, exactly, but about being haunted by the proximity of death that resides in danger. So, the stories do something akin to what supernatural monsters make happen in more speculative work. Am I onto something?

LMC: I never thought of taxidermy as “undead,” but I love it. In this region, the barriers between dead and not-dead are fuzzier. Places feel haunted, or let’s say, occupied, and the attitude is, well, they were here first, so it is what it is. It’s comforting to think that the ancestors are nearby. For myself, it’s something that I, a mere mortal, can neither confirm nor deny. I do wonder if these types of places counterbalance the disappearing with the acceptance of ghosts and other presences.

AW: Yeah, there’s this sense of foreboding in the landscape, especially in the early stories and then it just accumulates.

LMC: Definitely. I needed the early stories to set up the landscape, its harshness. Without that, “Tire” on its own could feel unfinished or even magical, but people do go missing. No crime—they are just gone. There’s a whole lot of nothing in the mountains, and in winter, one misstep, and that’s the end of the story. It’s not a landscape that will take it easy on a person, and it’s a place people go to in order to disappear.

I wanted those first two stories to set up the challenges of rural high mountain desert places, as well as how hard the landing can be, what must be earned. I had a spinout on a road like that one in the story (“Tire”), with a car full of kids, and it was terrifying. The winds and whiteouts in winter are crazy (but also beautiful). It’s not all Georgia O’Keefe and yoga, in fact, that’s just a small fraction of Northen New Mexico. I also hoped in these stories, and others, to give credit to the folks who have been there forever, and also to the land itself. I needed to set the groundwork, how harsh things can be, but also that it’s a vast area with many miles to vanish into. Once those facts are in evidence, the stories should feel less magical, and I also hope, the reader is accepting of the not-knowing.

AW: So, the magic—or the terror—is really the landscape?

LMC: I see place as a major character, of course, but I see it as both antagonist and protagonist. I wanted stories that could happen nowhere else. Part of that came from a love for both Northern New Mexico and coastal Northern California, which is featured in a few stories. Both are so weather-dependent (maybe weather is another antagonist), and I wanted the ways characters behaved in those landscapes to be a feature in their shaping.

There is something in John McPhee’s Annals of the Former World, which is an omnibus of his five volumes that trace the geological survey across the 40th parallel. I listened on a road trip across the U.S. that essentially ran that path along Route 80. Doing that solidified how important setting and place are to us, and therefore critical to storytelling. When in South Dakota (on a dip north) when a buffalo smooshed its nose on my window, and I was yup—we’re all landscape. Of course, that type of experience makes a person realize how small they are, in time, in a vast landscape, but it also made me feel a part of the massive story.

But the smooshed buffalo nose also has me thinking of the humor in When Were Hardcore. Characters make wisecracks, and the situations can be delightfully absurd. How do you find humor or joy in situations that are traumatic or sad? Why do you think it’s important to do so?

LMC: I am an avoider, for sure, so there’s that. I like the absurd, the off-kilter, so in my personal life, humor is a strategy to come at things from an angle. When I was young, around grade school years, I was told it wasn’t a very feminine way to be, which probably made me bear down.

When humor and pathos collide it’s always a shock. It makes people feel uncomfortable after a few beats, which I think works—we’ve become desensitized, so rather than going towards spectacle, I try to disarm.

All pathos all the time might work for some, but I don’t think it’s useful in life, and in writing where the ways to move are limitless, why not enjamb things that seem like they don’t “fit”? I have been told that my humor doesn’t belong in certain kinds of pieces, but I’m not going to change that sensibility. I’m a big deflector.

AW: There’s another kind of juxtaposition. For example, the ending of “The Tides Were Within Him” is both devastating and beautiful in an unexpected way. You kill the fireworks but make the ashes beautiful. You kill the plane but give a stunning description of its corpse. Why does the beautiful haunt the tragic, or disappointed, in such a way?

LMC: There were so many visuals I was considering, particularly exquisite damage and aftermath. We all love a beautiful wreck, right? I have never understood fireworks, the unmitigated spectacle of it all. But the way metal crumbles? Now that is interesting.

I’m captivated by the nexus of these things. Beautiful plus tragic gives us something to wonder about. It stranges us. Straight-up beautiful or wall-to-wall tragedy is single-note and doesn’t feel true. I also believe all art, but writing in particular, is about noticing and describing (while allowing a liberal interpretation of what “describing” can be). In paying attention to the world you see it all: beautiful, damaged, tragic, epiphanic.

The beautiful against the tragic is interesting because they are not opposites. Consider this: on the color wheel, there are compliments. Red and green, orange and blue, yellow and purple. Abutted, in the proper tone and saturation, they naturally play off each other. Then there are secondary compliments. They do the same thing, but in a subtle way, like ricocheting at a funny angle. You can make these weird combos, say acid electric yellow-green and red, or brown and lilac, or maroon and red. It’s friction, frisson, even the sense of movement. That’s what I am hoping to get, but with language and story.

We’ve been talking about juxtaposition, contrast, and the fuzzy in-between that happens inside many stories. There’s also movement between them. While the early stories spin around significant deaths, impending deaths, assumed deaths, the later ones become about recovery from illness, rescue, and even birth.

LMC: I was thinking of second, third, even fourth chances, which can be a type of rebirth. We have the possibility of multiple lifetimes. I’m not talking about reincarnation, but the turns we either choose or have thrust upon us.

With “This Snow, This Day,” I wanted an unadvisable move to be the choice, maybe the only choice, to hold salvation. For the narrator, absurd as it might seem, the lack of agency over their own body, was a sort of death. Maybe that overstates it, but I hoped to show that a person can be “cured” of a thing, but also not be, because of the psychological burden. Also, being forced to be indoors, for an outdoors person, is guaranteed to be a mental burden. Yet, if you are lucky to be alive, in the medical sense, you are expected to be goodness and light 24/7. You come out of surgery or get the cast off or finish rehab, and you’re supposed to be good to go. And that’s just not the case.

I wanted “Soon It Will Be Summer” at the end, because it has the most possibility. The narrator is truly lost, and definitely made some unwise moves, but even at the ending, where he is feeling shamed, there is an opportunity for him, as well as the folks he let down. Yet I didn’t want to write him towards salvation.

I also wanted to leave the collection with the idea that we stay in certain places, not because they are easy, but because we need to. Some of the other stories address the idea that arriving and staying in a certain place must be earned, and in turn, I wanted to think about when folks migrate away. It had to be someone truly of that place, so as to raise the stakes of leaving. I also was thinking about duty; like when can you turn your back to save yourself and what is owed. I still think about these characters, what their next story is, how they fare.

AW: Your characters are very often lost, down on their luck, or sort of caught in in-between stages of their lives. Things don’t go well for them—at least not in conventional ways. They’re mostly outcasts, but you write about with them with so much love.

LMC: I’ve always felt it was a good tactic to offer the most grace to the characters who have the hardest lives. Bret Anthony Johnson said (ages ago, so I’m wildly paraphrasing) to always adore your characters and remember that they are smarter than you (the writer). I do love them, particularly the ones in this closing story. It pained me to have them make bad choices, and I hope that the reader sees that, often, what looks like a choice really isn’t. This story wrecked me in a way, because I knew there couldn’t be happiness, at least not in what I wrote. But there could be, later, in the reader’s imagination.

I’ve noticed, in the real world, that there is this immediate assumption that when someone is in dire straits, that they did something to get there. It’s easy to look at a teen mother or a kid who ends up raising themselves, or someone with a mental limitation, or even someone who appears to be a ski bum—and land a judgement of fault. I want to offer my characters, who I love like they are family or my close circle of friends, all the grace I can, yet not let them off the hook.

AW: The final story—in a book that I really believe is so much about death—is about a birth (but it’s not precisely joyous) and it ends with a character setting out on a new beginning (but with a whole lot of regrets). Is this a happy ending in your mind or is it a tragic one?

LMC: I don’t think it’s happy, but I hope it is full of possibilities, which is a more layered kind of happiness. I imaged Ez conflicted, because his screw-up led to his way forward, and I hope I wrote the character well enough that the reader would think this. There can be a redemption, and maybe the leaving, for now or forever, is a step, but it hasn’t happened yet. I also didn’t see tragedy, because given all of the missteps, I left the characters in the best places to move forward. The happiness might be that the story contains a few latent heroes. A tidy and or happy ending for these folks at this stage seems impossible, so I never wanted to write that. Life (meaning me) bore down on them too much for that. So maybe a third thing: an ending of possibility, one that keeps the doors of the story open.