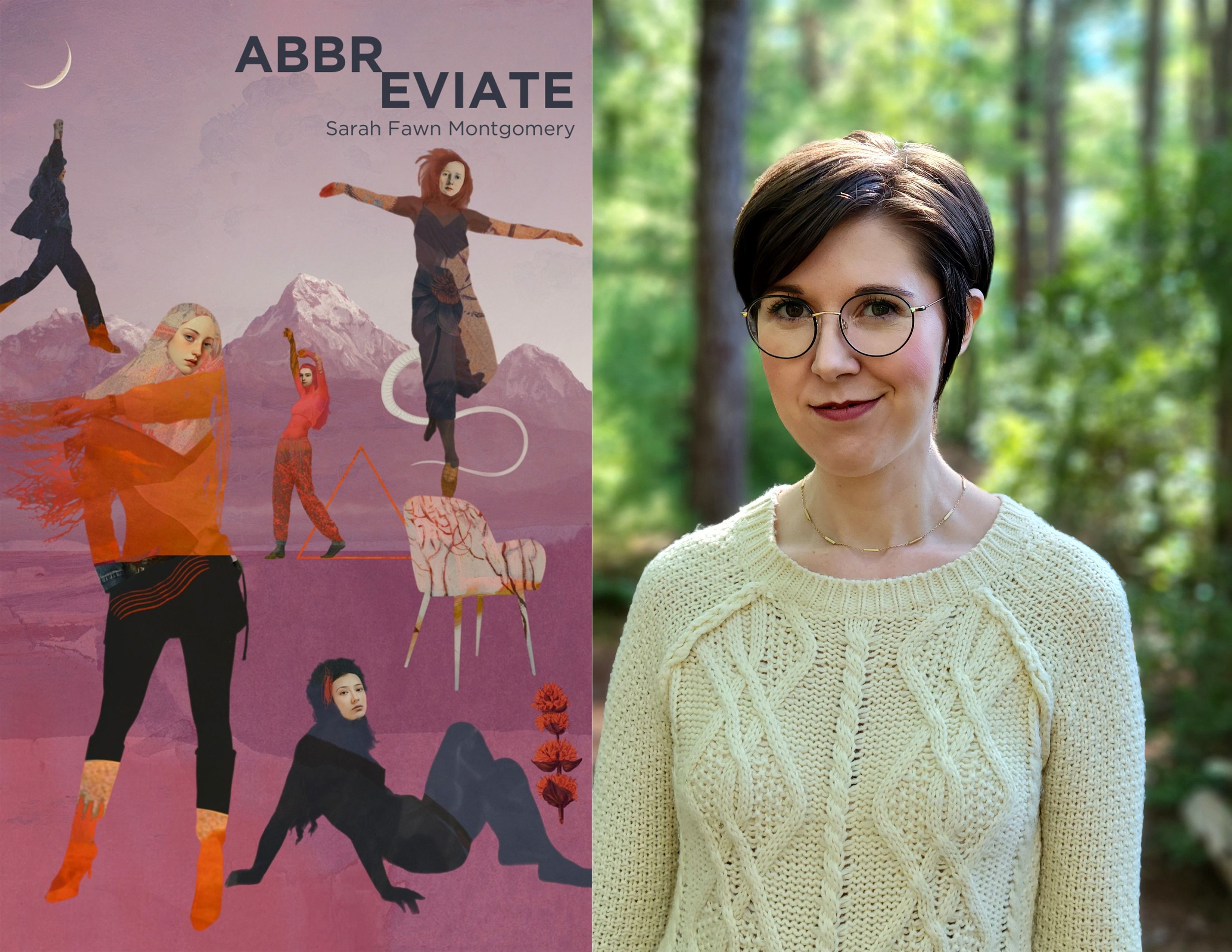

Juliet Way-Henthorne: First, something fun! There’s a gorgeous throughline of superstition, ritual, and small acts of rebellion in Abbreviate. What’s one small belief or habit from childhood that you still think of, even now?

Sarah Fawn Montgomery: I love this question! Growing up, I took a lot of satisfaction in the rebellion of keeping things to myself. I loved the rebellion of thinking and feeling and believing whatever I wanted, especially if they were things others did not approve of. I liked to mull things over in my mind and then write them down because as a child writing felt like the ultimate rebellion, a way to claim space on the page when the adult world sought to deny me this in real life. I’ve definitely continued this into adulthood as I’ve pursued writing nonfiction. Sharing truths about my experience through writing seems like the ultimate act of rebellion, especially if these truths are things those in my past denied or required me to keep secret, or if they are things the world does not value, like the stories of my girlhood and womanhood I share in Abbreviate.

JWH: The hometown feels vividly rendered—at times like a character, at times like a mythic or forgotten landscape. It made me think of dry-earth places that feel suspended in time, almost Martian in their stillness. Can you talk about how you approached writing setting in these essays? Did you set out to give the town such presence, or did it emerge organically as you wrote?

SFM: Place has always been an essential way I process memory, and it is a deliberate part of every piece I write. I understand myself in relationship to my surroundings, so when I was growing up, the arid isolation of my hometown seemed to mirror the desolation of girlhood. As I describe in some of these essays, there was little water or growth, little opportunity for both the land and the girls and women who made their homes in it to thrive. Predators filled the landscape, just as they filled our schools and homes, girls and women constantly under attack by boys and men, constantly on edge as we tried to avoid danger.

And yet the girls and women I knew tried to make something beautiful in this place. They grew gardens in desolation, discovering ways to keep things growing despite the environment. They watched bats come out at night, plucking sustenance from the air before darting away to safety, and they learned how to survive in similar ways. Young girls who were brutalized by the place found ways to take comfort in childhood games, pretending they were small enough to fit inside dollhouses or looking at the skies to imagine themselves free and safe in the constellations. Teenage girls made magic during middle school sleepovers, the otherworldly glow of the black light making them powerful, or they took up space and found safety in the imagined landscapes of school projects, places that were nothing like the ones we came from. And though I fled the place as soon as I became an adult, it has never really left me.

JWH: The last lines of “Stomp” absolutely floored me: “How all around us was dead. How we had to tiptoe to escape the snakes.” It reads like a thesis statement whispered from the edge of girlhood. These lines appear at the very end of the first essay, but they echo throughout the collection. Did you always know “Stomp” would go first? How did you approach the ordering of these essays?

SFM: Though the collection is organized fairly linearly, moving from childhood to adulthood, I was careful to include some variation in the structure to amplify certain themes or images, to create echoes and ghosts. Because this collection explores the way girlhood trauma impacts women’s lives, I structured the collection to mirror this experience, while also having enough movement so as not to be predictable. Structuring this book was often a game of Tetris, shuffling pieces into different positions to see how one ending led into another beginning, how certain images or ideas or characters were strengthened or modified depending on placement.

But there were certain pieces I considered anchor points. “Stomp” is one of those pieces because it combines stories of girlhood and womanhood in its exploitation of my childhood play with my aunt and the ways we were both hurt by her husband and haunted by his actions. I also started with this essay because it introduces the idea of being trapped in gender expectations and abusive relationships, as well as the contrasting idea of turning to the sky and space for freedom and escape. Another essay that had a clear placement as the final piece in the collection was “Men Teach Me How to Play Dungeons & Dragons.” This essay shares my experience learning to play the game from a friend’s husband, who grew increasingly patronizing and aggressive when I would not follow his expectations for the imaginative game. I ended the collection with this essay because the use of play mirrors the play in “Stomp,” as do the gender roles and suggestion that girls and women—no matter their age or life experience—are always expected to obey men and always in danger.

JWH: There’s something so intimate and implicating about your use of second person, as though you're speaking not just to the self but to a ghost self, or to the reader directly. What draws you to second person? Did it feel risky or necessary?

SFM: I used a range of points of view throughout this collection—including first person singular, first person plural, and second person—because I was interested in writing about my intimate experiences and the collective experiences shared by many girls and women. I like the way point of view encourages readers to reconsider their ideas about authorship and ownership, especially when it comes to stories about violence and injustice. As you mention, many of these essays are about former selves, ghost selves, ways of thinking about our past that are no longer possible, or the stories that haunt us in the present and threaten our future.

Quite a few pieces in this collection utilize second person because I like the distance this provides to the reading experience, as well as the protection it provides to the author. Second person can add a feeling of detachment in work that is exploring these themes, amplifying them through this craft choice. It can also provide the distance needed for readers and writers to engage with difficult subject matter. The essays in this collection that utilize second person explore childhood neglect, domestic violence, sexual assault, and sexual harassment, all of which I needed some distance from in order to be able to explore. Because these were also stories that readers may have experienced as well, utilizing second person allowed them to imagine themselves as the speaker, while also allowing me to speak directly to them.

I don’t consider the use of second person to be a risk because all writing is risk, especially when you are writing about the self, especially when you are writing about trauma. Why write if you are not going to take a risk? Why share our secrets, shames, and selves if not to risk it all in order to reach readers? Sometimes the act of taking a risk the reader can recognize is what compels the work at all.

JWH: The book is called Abbreviate, and throughout, there’s this tension between what’s said and what’s left unsaid. Can you speak about the role of silence or omission in your work?

SFM: Growing up, I was often told that little girls should be seen and not heard, which reinforced that for a woman to be of value she must be silent. This was also reinforced by the fact that I rarely saw the stories of girls and women given the same weight as those of men. Girlhood play and domestic labor were considered secondary to the games of boys and careers of men. I watched as boys and men took up space with their stories, interrupting, correcting, and speaking over girls and women until we learned to shrink, to believe that our stories were not of value, even to ourselves.

As a result, I rarely spoke up about things that were important to me—girlhood games, childhood crushes, my dreams and desires. And I learned not to speak up about things that should have been important to adults—abuse, assault, predatory mentors—but that no one wanted to know. My silence was more about my compliance than my safety, more about the comfort of others than my own ease. I learned to shrink, to abbreviate my stories and my life so that I could be a good girl, a good woman who did not claim space.

Many of these essays voice what I previously kept silent by choice or was asked to keep silent by adults, by abusers, by misogynistic society. Writing them is a kind of resistance, a claiming of space on the page when I have not always claimed it in my life. But there is much left unsaid in these essays, omissions that ask readers to consider what is implied, vacant, empty, absent. These holes ask readers to consider whether it is possible to live a full life when girls and women are so empty. There is also silence and omission in the short form of essays that often pack large subject matter into just a few pages to reveal what it is like to be told by the world that you must be contained. I like to think of my work as a way to push back against imposed silence but also to claim it as a source of strength.

JWH: Being from California myself, I recognized so much in the details. But this isn’t the romanticized California we often see. It’s haunted and strange and urgent. What does California mean to you as a writer? Has that meaning changed over time?

SFM: I grew up in California and it always features prominently in my work. It wasn’t until I moved to the Midwest to complete my PhD, however, that I began to recognize the disparity between the idealized representation of the state and my experience growing up there. California is often represented as a happy safe haven full of beaches and theme parks and opportunity, but this romanticized sheen quickly wears away when you realize how much of the state lives in poverty, how drought and wildfire have ravaged the landscape, how the artifice of celebrity is a danger to the girls and women who live there, big business protecting predatory boys and men.

I want to reveal this stranger California, a place haunted by history, a place where things are not what they seem. As a nonfiction writer, I’m particularly interested in artifice, in the ways this place has been written and sold, in the ways truth is murkier and more cynical. I’ve always felt an urgency in California, a struggle for survival, and the longer I live away from this place (I now live in the greater Boston area), the more my home state morphs and changes, and the more important it is to dismantle the myth of California.

JWH: There’s so much sharp, sensory attention to girlhood and bodily experience in this collection—injury, appetite, shrinking, eruption. How did you balance the visceral with the lyrical? And how did you ground and keep yourself safe while revisiting and reembodying these feelings and experiences?

SFM: The best way for me to explain emotion is always to take it to the body. It isn’t until I describe the body that I fully understand the intuitive or intellectual. When I’m writing, I ask myself what my body was doing while something was happening or while I was feeling a certain way. Then I reverse this and ask myself what I was feeling when something was happening to my body. By considering both sides of this equation, I’m able to more fully render my experience on the page.

There were a lot of elements of craft that allowed me to protect myself while writing about painful emotions and experiences. Both the short essay and the short collection allowed me to write about complex material in a contained space. Similarly, using a plural first person or second person point of view allowed me the distance that was sometimes required to be able to write about certain subjects. Other craft choices—like focusing on toys or games, planetariums or museums, school projects or amusement parks—provided an external focus and an anchor point for me to return to when writing about difficult subject matter. All of these craft choices acted as protective barriers to keep me safe when revisiting certain subjects, as well as touchstones for me to hold onto when writing about challenging material.

JWH: Many of these essays take place in highly performative spaces: classrooms, lunchrooms, the gym, the screen, the page. Girls are actors in their own lives, often caught between audience and author. How do you think girlhood teaches us to perform? And what role does writing have in undoing or restaging that performance?

SFM: So much of girlhood play is grounded in performance. Things like playing dress-up, playing kitchen, playing dolls, playing ballerina and so on all require performing specific roles with rigid requirements and a judgmental audience. Encouraging girls to participate in this play reinforces that even their imagination requires correction and that their lives will be ruled by criticism and critique. And it is not just play that encourages performance. A girl’s very existence is framed as performance with specific requirements about smiling, being polite, being good, and a range of other behaviors, all of which are designed for external validation rather than internal satisfaction.

Because girls learn early on that performance is their only source of power, writing becomes a way to restage this performance. When the roles assigned to you are written by others, it can feel as though you have no choice but to accept them in order to survive. But learning to write your own stories, to claim your worth through words and create power on the page is a powerful act of reclamation. Rather than becoming actors in their own lives, girls and women who write their own stories are no longer caught between audience and author but rather shape their lives through purposeful agency.

JWH: From jump rope chants to Dungeons & Dragons to video games and Tetris, there’s an undercurrent of games and codes running through Abbreviate. The stakes of these games feel impossibly high. What draws you to the language of play, and how do you see it operating in this book: as coping, rebellion, or something else entirely?

SFM: I’m drawn to the language of play when writing about girls and women precisely because they are not afforded this luxury. While boys are encouraged to be imaginative and expansive in their play, loud in their games of war and victorious in sports, young girls are taught domestic labor and gender expectations disguised as fun. They diaper pretend babies and cook in pretend kitchen. They play dress-up and take dance classes where they are encouraged to focus on outward appearance and strive to be slender. It is no wonder these attitudes persist into adulthood, men continuing their leisure while women continue the same domestic labor they have performed since childhood.

In Abbreviate I was especially interested in exploring this division of play, as well as the subversive ways girls and women play despite strict societal expectations. Reclaiming the language of play is a reenactment of lost childhood, as well as an act of rebellion. Because so many girls are denied childhood by unfair expectations about domestic labor, utilizing the language of play and making space for playful memories, however small, can restore what has been lost. Similarly, incorporating this language in stories of adult womanhood is a reminder that we can resist unfair expectations that seek to silence our imaginations and stifle our creativity. It is an act of rebellion to claim play as an adult, to insist we have the right to leisure in a world that argues this is selfish and to claim joy when so many aspects of society seek to strip it from us.

JWH: Many essays return to the same emotional pulse points—hunger, shame, defiance—but through totally different lenses. How did you know when you were circling something you needed to return to versus when a piece needed to stand on its own?

SFM: This collection explores haunting, compulsion, inherited trauma, and legacies of abuse, so it made sense thematically to return to certain ideas, memories, and experiences in various pieces. Sometimes I returned to a pulse point because my age in the collection changed, thus impacting the way I viewed a particular experience. Other times I returned because I wanted to offer a new experience with a similar theme, collaging various memories together until the complete picture of a particular idea emerged. Sometimes I returned to particularly painful memories in various pieces to replicate the ways they have haunted me.

It was important, however, to make sure I didn’t fall into repetition too much, so I made sure to orbit around repeating themes as opposed to repeated memories. Similar themes appear in essays from childhood, my teenage years, and young adulthood but move in very different ways, illustrated through very different experiences, which allowed me to offer fresh insights and reflection. I tried to let themes guide me in determining whether piece could stand on its own or if it needed further layers of analysis. For example, an essay about playing video games as a girl and later as an adult woman, when gendered expectations about domestic labor makes leisure time impossible, could easily stand alone. But stories about the abusive romantic relationships my friends and I experienced growing up needed to be explored with nuance and from many different angles.

JWH: In essays like “Mystery House,” we hear from an older narrator—someone who has made it through girlhood but is not unscathed. There’s a retrospective clarity in these pieces, as if they’re not just telling the story, but reentering it with new language. How do you think about voice across time in this collection? Were there essays that called for an older narrator to step in and interpret the ruins, so to speak?

SFM: I’ve always considered time as fluid as genre or gender. This is why so many of these essays—regardless of whether they are about girlhood or womanhood—are written in present tense. I’m interested in reentering a memory from the perspective of the me who lived it, as well as the perspectives of various selves I’ve been since, layering perspectives in a single essay. We contain all the versions of ourselves that have ever existed, so this layering of voice on the page is reminiscent of the way we experience the self throughout our lives.

But some essays require an adult perspective. “Mystery House,” for example, which is about an emotionally abusive relationship in college required a more nuanced understanding of the ways abuse manifests. Because I had witnessed domestic violence and more extreme physical forms of abuse as a girl, I did not understand at the time how manipulation and control could be just as damaging. This required an older narrator to reenter the memory and interpret the ways it ricocheted throughout my life. Several of the other essays in the collection do the same, an older narrator revisiting the past to write down the wounds and make sense of the scars.

JWH: This book feels so cohesive, so precise: what was your revision process like? Did you write many of the essays in quick bursts, or were they years in the making?

SFM: This collection actually came about by accident. I was finishing up another book and wanted to play around with short pieces as a distraction from the other project I’d spent so much time writing. I typically write poetry and longform nonfiction, but I was interested in hybridity, which is why I focused on lyric flash essays. Most of these essays were written in a single short session, which is how I tend to write poetry as opposed to prose. I think this approach led to the essays’ precision and power, as well as their reliance on voice and image. Because I tend to be a bit obsessive, I started writing more and more of these flash pieces, though I never intended them to be a collection.

It wasn’t until I had written and published more than half of the pieces in this book that I realized there was a book at all. Then I set about filling in gaps, adding new narrative threads, and braiding images and ideas throughout the book structure. I think this approach to writing pieces—and later the entire collection—is really beneficial. Much like the game of Tetris I describe in the book, these essays all operate as self-contained time capsules, small building blocks or puzzle pieces that fit together. And this concept of play took the pressure off writing and allowed me to experiment with point of view, voice, time, image, structure, and my own expectations of what an essay or a book should look like.

JWH: Did anything surprise you in the writing of this book, not in what you discovered about the material, necessarily, but in how it asked to be told?

SFM: The book’s hybridity is what surprised me most. I’d written about some of these themes and memories in longform nonfiction before, but I only accessed some of the more difficult material when I began to write about it in poetry and fiction. Several of the pieces in this collection actually began as my earliest attempts to write fiction, though they would probably be better categorized as autofiction or even speculative nonfiction. These stories tended to be about particularly difficult subject material—queer identity, abusive childhood, predatory men—and blurring genre in a way that allowed me to escape the pressures of traditional nonfiction was what allowed me to write about them in the first place. Once I give myself permission to write about these subjects in poetry or fiction, I unlocked many others and embraced the power of hybridity.

JWH: Finally, what’s something you cut or dramatically altered that you secretly loved or still think about?

SFM: This collection was originally much more hybrid, incorporating poetry throughout. All of my previous books followed strict genre designations, so I wanted to confront the construct of genre and gender throughout the collection, using hybridity to resist and remake the stories of my girlhood and womanhood. Many of the poems touched on similar themes and images because I tend to write poetry and prose about the same subjects at the same time, and so they fit quite cohesively into the collection.

Ultimately, however, I decided to remove the poetry from the collection entirely because these flash essays are lyric in themselves, providing the hybridity I was seeking without significantly adding to the length of the collection. It was important to keep this collection small to illustrate the larger themes about the ways girls and women are taught to accept smallness in their lives and in the world. This version is the book I was always writing toward, but the interplay between genres in the earlier version was the experimentation I needed in order to arrive here.