Kristin Schultz: Out of the vast expanse of research included in your works, what was your process like when deciding which facts and ideas to weave into your stories?

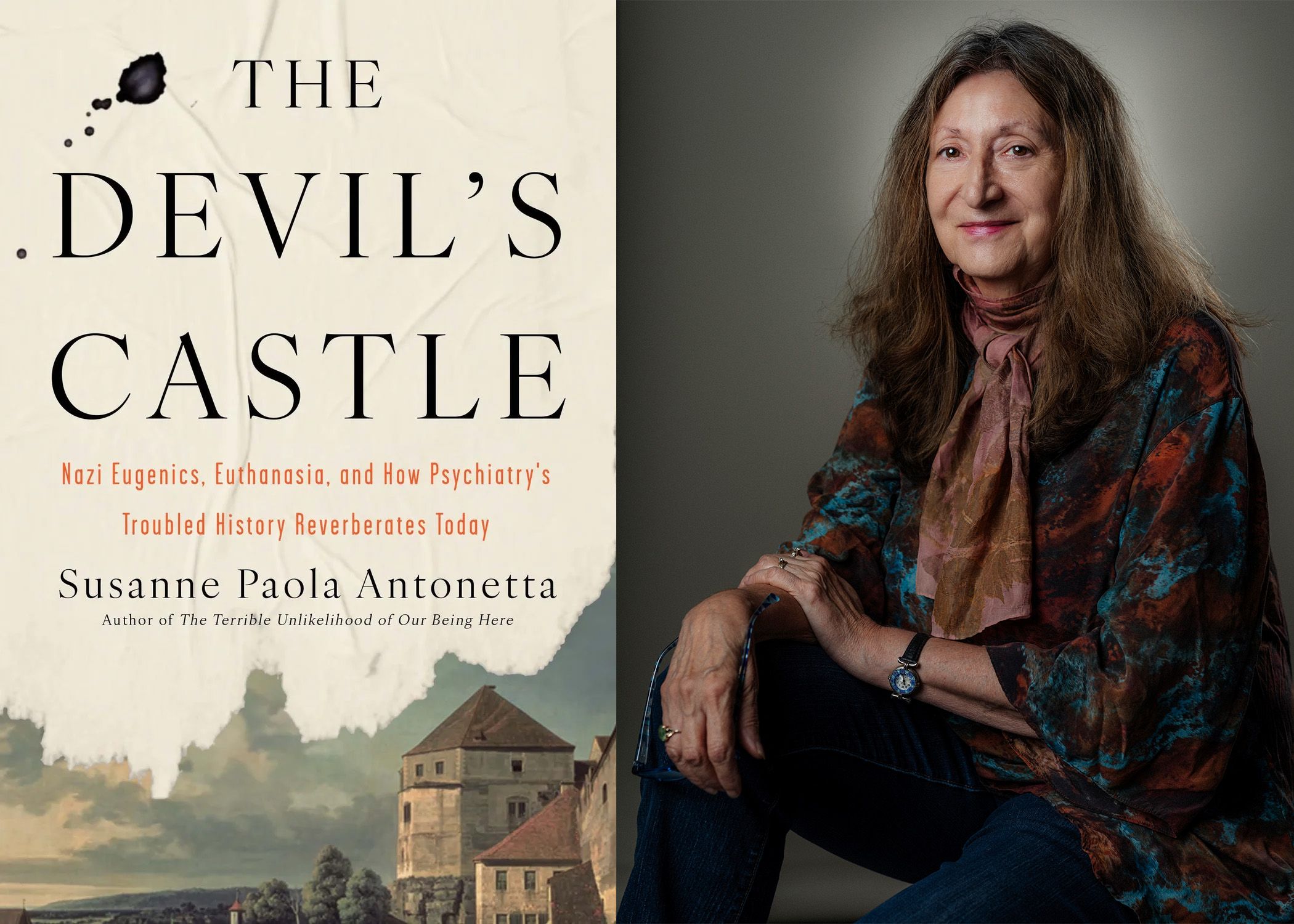

Susanne Paola Antonetta: Honestly, there’s no formula for that. In most of my books there is quite a bit of research, and there’s quite a bit more research left on the cutting-room floor. Some things I thought I would surely cover I ended up leaving out of The Devil’s Castle. Other things, like the Nuremberg trials, I determined I wouldn’t write about, then I did. I find readers are always necessary, but super-indispensable when evaluating research. I remember one of the readers of my first Body Toxic draft telling me my material on boiling-water nuclear reactors was just, well, boring. It was! Thank goodness he told me. Better to bore the one, and learn from it, than bore the many!

KS: What precautions can a new writer take to ensure they do not come across as unaware of the value of those around them?

SA: As to judging your own work--I think readers are very helpful, and I think it's a fair question to give to your readers: how do I come across and how do my other characters come across? If the feedback is that you seem like a great person in the midst of jerks, you are doing something wrong. I can promise you that no one is simply a good person in the midst of jerks.

Reread your own pages with the same question in mind. No one should be perfect. Everyone should be human. It's the hardest thing to do. But it's absolutely essential. I have read multiple manuscripts in the past year in which the author started sounding like they were writing a social media post--"my psycho mother" type of stuff. Not only is that boring and ableist language, but no one wants social media-level discourse from a book. We want nuance.

KS: What drives you to write?

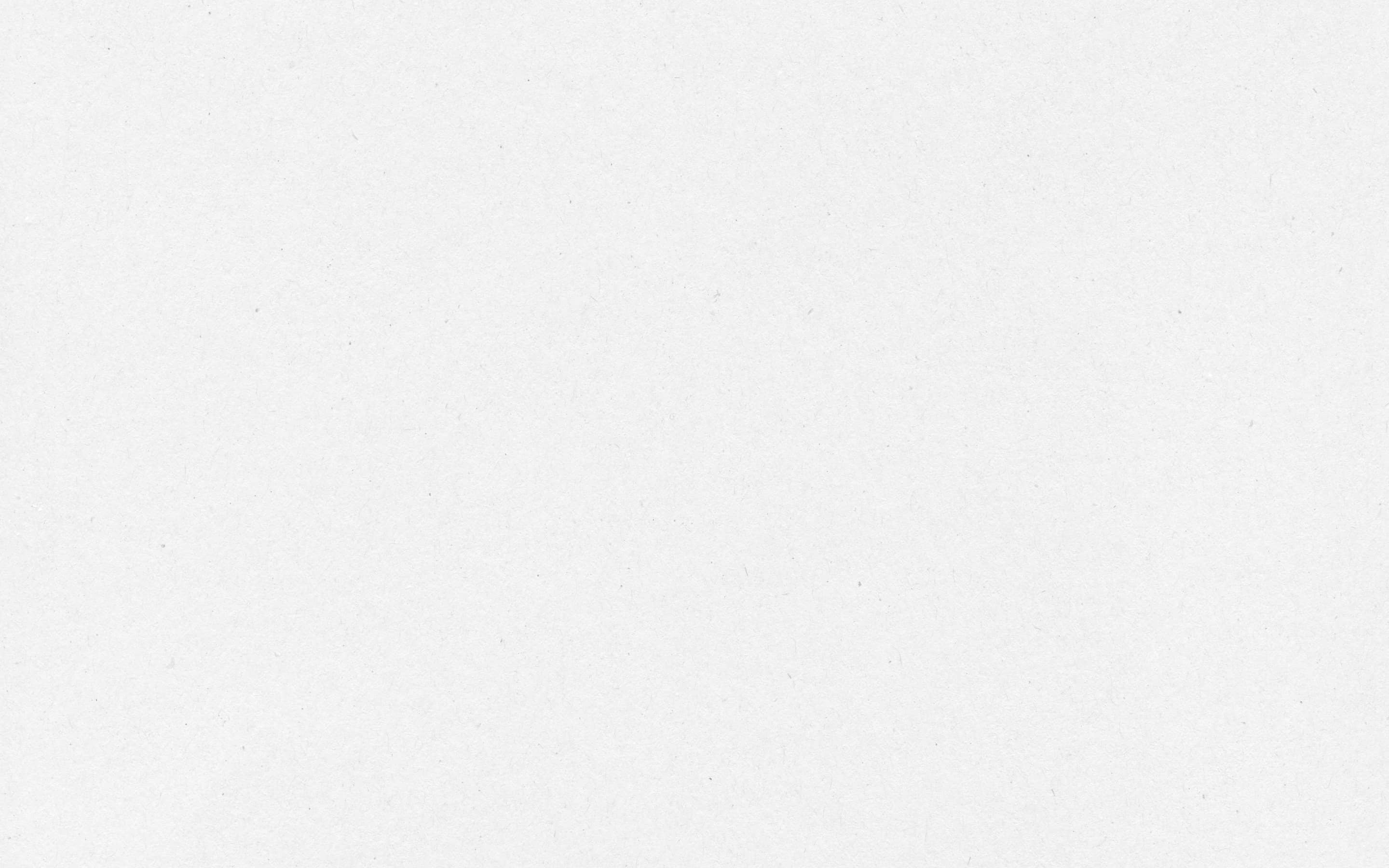

SA: I have wanted to write, I think, since I learned language. I moved within the last two years, and it was entertaining to find my old pages of poems, stories, song lyrics and plays, dating from the age of six. I’ve always loved to read, also, and when I read books that mattered to me as a kid, I loved that sense of connection with the author—that you are together in a world you’re co-creating. It felt like a very pure, vulnerable, very human connection. I wanted to have that experience as a writer.

With a book like The Devil’s Castle, that sense of connection is amplified by the importance of sharing this history and preventing the world from falling back into that eugenics level of error. It feels to me as if neurodiverse people are still under attack—not just in the lack of decent care, though that’s huge, but in the social myths of mental illness causing violence, of people with autism as this drain on the population. It’s time to set the record straight and figure out how to do what works. If I can move that forward even a little bit, it’s so worth it.

KS: Is there any connection to the timing of your writing of The Devil’s Castle to this time of political tumult within the United States?

SA: Unfortunately, unless you self-publish—and in some cases even then—you don’t have a lot of control over the timing of a book release. In the case of this book, COVID interrupted my research and caused the book to come out several years later than it was originally scheduled to run. And the timing of placing the book with a press, which was done on proposal in this case, is also out of the writer’s control. That being said, the book came out at a time when its relevance is heavily underscored. The rapid deterioration of a fairly liberal culture—Germany in the 1920s—the demonization and othering of those who are different: it does feel tremendously timely.

KS: In many of your books you talk about your experiences with the mental health system, at times delving into intimate and vivid details about what those experiences have been like for you. What role did including these specific details about your personal experiences have?

SA: I say in the book that my community has never had its acknowledgement, its “never again.” After the Second World War so much of what happened to the neurodivergent population, and the way Jewishness was connected to that population, was whitewashed out of the story. The other side of that lies in the story of my two neurodivergent models—Paul Schreber and Dorothea Buck. No one could fully understand them without having been mentally different and in a similar messed-up system to the ones they fought. So, while I am a minor chord in the book, my lived experience in this world is tremendously important.

KS: Do you have a specific audience you are hoping to connect with and how does that shift depending on what you are writing?

SA: I find it’s a process. It takes me a while to even define who I might be writing for, so my first audience is myself—Joan Didion’s “I write to find out what I think.” I don’t think about audience at first. I’m working on a project now that’s in early stages, and it deals with Shakespeare’s mad characters and fools. Someone asked me if I was going to explain the plays for an audience that didn’t know them, and the need to do so hadn’t even occurred to me. I know the plays, so I hadn’t really worried about that. As I go, more will emerge about who else might be interested and what I have to do for that audience. Audience is a later-stage question, and the answer will affect how I complete the book, but right now, I’m just exploring.

KS: Do you initially write just for yourself—to make your own discoveries or answer questions you’re curious about? Would that be gratifying enough even if you didn’t get a particular book published?

SA: This is such a good question, one we don’t ask enough, as it’s hard to get books published these days! According to the Random House anti-trust lawsuit, the majority of books published now in the U.S. are self-published, which interests me a lot. I think any writer who’s been doing this for a while ends up with stuff piled up, they haven’t been able to place.

I think the answer is that I do initially write for myself, and I do make discoveries and figure things out through the written word. I can’t imagine writing an entire book and just leaving it at that, however. I mean, for me the revision process is huge, and it makes up most of the time I spend writing. Most of my books go through a radical change during the last stage of revision, which is often within six months or so of submitting the manuscript to the press. I’m not sure I could get through all of that and then happily let it languish in a drawer! I also wonder if that last, radical stage—which for The Devil’s Castle was the introduction of neuroscience—would happen without a publishing deadline. So, I don’t think that last piece of work, which is often the most gratifying, would happen without any thought of publishing. That said, I would find selfpublishing a perfectly fine option.

KS: Do you have a strategy or technique you use to stay on track and continue to produce these impressive books?

SA: The Devil’s Castle took me around seven years to write, and I didn’t do much else while I was at it. I always have more ideas than I can get around to. And I do work every single day, though sometimes not on weekends. As David James Duncan always says, it’s ultimately a matter of ass in chair! If you’re not there to work things through, all your wonderful ideas are going to dissipate.

I’m also a fan of carrying notebooks with me everywhere. I’m kind of a hopeless eavesdropper and I write down anything that strikes me.

KS: What attracts you to writing across genres?

SA: I think I’ve tended to cross genres when I hit on the limitations of one, or what I feel as limitations. I worked on poetry until I wanted to tell a more expansive story about my family—it just wasn’t fitting into the poems, so I began to write nonfiction. Telling those family stories became the germ of my first book of nonfiction, Body Toxic. When I write fiction, which is the genre I’ve done the least, I tend to have hit a wall with what’s factual and feel the need to change things around. It’s kind of like, what if this experience happened to a very different type of person?

For the past year I’ve been working almost exclusively on poetry. And I can’t exactly explain it, but the shift had to do with Helene. There was something about that storm and its aftermath here in Asheville—such a stark reminder of how the earth under your feet can literally rise up, throw you off, become something else. And at the same time, you see in some of the people around you such a stark, almost improbable, good emerge. I am not writing directly about Helene, but somehow poetry seems more suited to extremes.

KS: How do you take care of yourself when writing about difficult topics?

SA: Oh lordy. Such a great question. Such a hard one to answer! I have a hard time trying to take care of myself in the best of times—something about coming from a Christian Science background, and a very sexist one. My first impulse is to push through. But I did do things like visit gas chambers and interview survivors for this latest book, and while I can’t say I healed myself by forest bathing or anything too intentional, I definitely had to take breaks. And I tried to be intentional about appreciating the people who represent the good. It’s easy to imagine going along with evils when they’re promulgated by your government, but what makes a Fritz Bauer, Johannes Warlo, Dorothea Buck? Their work on behalf of others, with so much at stake, feels utterly extraordinary.

KS: Do you have trusted readers or editors who offer feedback on your work before submitting to a publisher?

SA: Yes, I show my husband Bruce Beasley pretty much everything, and vice versa. He is a brilliant reader and always my first sounding board. We are completely honest with each other about our work. A “sorry but this isn’t finished yet” from either one of us sends us back to our desks, but we never feel less than appreciative about the feedback. It’s so important.

After that, I have had various second readers for my work, and it kind of depends on which of my writer friends are available and which might be good readers for that project. I usually wait until later in the project before approaching anyone else. If my agent Jill represents the book—she doesn’t always—she will provide feedback as well.

KS: What advice would you offer beginning writers of creative nonfiction in terms of sustaining a career in the genre? In other words, how would you suggest the best way for a beginner writer to understand that they don’t need to write their whole life in their first memoir?

SA: That is such an important thing to understand! I am currently reading nonfiction manuscripts evaluatively for a press I work with, and I am finding many writers can’t remember that key rule, “not your whole life.” People say their book is about this one particular thing, but then there are chapters upon chapters about how I loved this Disney movie when I was three and I had a hamster named Sparkle etc. etc. So much that’s not relevant, and you can see the author kind of thinking, But that’s how it was!

So, yes, always remember that with fiction you build a world from the inside out, but nonfiction goes from the outside in, and there’s going to be way more on that outside than you need. What of your experience is completely relevant to the concerns of this book? Start with that. Unless you became a vet, Sparkle may not need to be there.

The other thing I’m finding—and I’m right in the middle of this reading so it’s on my mind—is book manuscripts that have a lot to recommend them, but in which everyone is deeply flawed except, as it happens, the author! I’ve read manuscripts in which the author goes through the political beliefs of everyone else mentioned, critiquing them. Often with no relevance. These are—I dunno—Facebook posts maybe? Read over your work and if you’re the only good person with values in there, something’s very wrong.

Another piece of advice: listen for what other people find interesting about you. It’s easy to overlook the things in our lives that have been truly extraordinary. And don’t be afraid to approach writers you admire, with some humility of course. Many writers are generous people who like elevating others.