If you look up past the thick concrete, there is a square of cloud and sky. The muffled bustle of traffic taunts beyond the walls.

Funny they call it a courtyard. Nothing is green or growing; it’s more like a human kennel with a skylight. Sally, a young blonde with eyes magnified by thick glasses, strides back and forth, suddenly motivated to exercise in a space two metres wide. Like a caged tiger with its powerful gait reduced to pacing, it’s more depressing to see her move than sit still. Limited to walking in circles, anyone would look mentally unwell. But this place is very much about role-play. We are the crazies here to be fixed by the capable staff.

I look up at the perfect sky until it’s too much. This is not a place of healing. This is a holding tank for flight risks like me: a punishment.

Sally continues to pace, determined to take control of her life. But in only a few minutes she’s slouched over and silent; stares into a dimension unreachable to the rest of us. This is what tall concrete walls do. We are all, in many ways, a reflection of our environment.

Vermilion rhododendrons frame the glistening Himalayas whose vast proportions command reverence. Tendrils of mist quiet the moss-covered trails and we gladly surrender to the mountain’s spell. Hours upon hours we walk with nothing to do but push our bodies forward, scaling the sides of valleys until moss gives way to ice and snow and we gulp shallow air that leaves our lungs craving more.

What kind of magic (magical thinking?) led to me being here, walking amongst friends who joke: “We get on because we’re all a bit unhinged,” “That’s why I love her, there’s never a dull moment,” “Normal is for chumps.”

Travel was unimaginable: future clouded with mandatory psych appointments, side effects and prophecies of chronicity. But I am here, the rhythm of our feet beating against the earth underneath stanzas of laughter: “Three hundred rupees into the pot every time you trip and fall, two hundred if you let one rip!” “Five hundred if you get leeched!!”

By day seven we’re hacking over steaming bowls of water as our guide, Kalsang, covers our stuffed-up noggins with blankets. Giggling at our lumpish forms, he announces we’ll stop at a mountain village to rest and recover.

But I’m not recovering: one step, two step, maybe the ache in my bones is from the altitude? Maybe if I kept going to bed early every night, instead of making out with the hotel manager on the rooftop in between rows of linens blowing in the night, and god he was beautiful, and vapid, and too persistent, and wasn’t I always getting into bad situations and getting out of them not entirely unscathed, and wasn’t that also the start of the madness? Maybe I haven’t learned to love myself enough yet—boundaries thin like a weakened immune system.

When we reach Pokhara at the end of our two-week trek, a friend drags me to the nice tourist hospital. She fills out the paperwork for me: despite the muggy air and my layers of jackets, my hands shake too badly to hold a pen. The doctor, who has seen a lot of stupid and stubborn tourists, says I have the clearest case of pneumonia he’s seen in his career. It’s moved through my crackling lungs into my bloodstream, causing inflammation in my vital organs. When the vomiting started five days ago—curled up by the toilet, in ditches beside tea plantations, spit and laugh it off because no one likes a whinger—my body was experiencing sepsis, organs on the brink of shutting down. I should’ve been helivaced out of the mountains days ago, but my body remembers the last time I was in a hospital bed, and I kept walking forwards because I couldn’t, couldn’t go back.

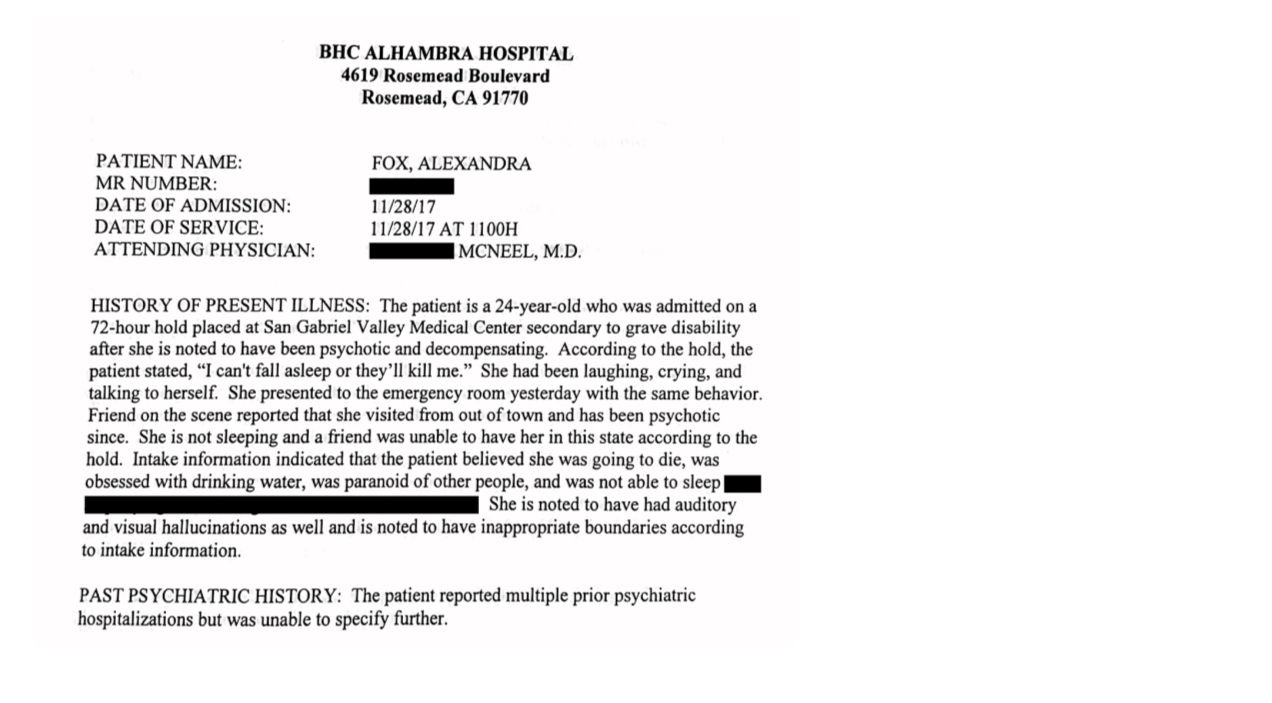

A new psychiatrist with coiffed hair breezes into the sterile room and glances up from my file, noting my glazed eyes and disorientation from the three orange tranquilizers they gave me the night before. She assesses me for a few minutes, shuts my file, and declares, “I’m sorry, Robyn, but you’re exhibiting early signs of mania and are likely having your first schizophrenic break. I can’t let you leave.”

I clear the crust from my eyes and wonder if I’ve heard correctly.

What brought me to this cold place doesn’t feel like mania but an insuppressible unravelling. For months I’ve been convulsing for hours in the night, waking up (if I slept) to the sound of the bolt on my door sliding open, pools of sweat between my breasts. My body flees over and over as if the first time wasn’t enough. (If in sleep our dreams are as real as waking reality, does that mean I’ve been attacked a hundred times now? A thousand?) Dozens of prescribed pills have only brought a rising background cacophony, unformed voices threatening to take control of the helm. Can’t focus, can’t read, can’t speak, short-circuiting. Fearing the fall towards oblivion, I've come here hoping for a test, an MRI, a tangible explanation and a straightforward cure.

“The psychiatrist from last night said I could go home this morning,” I tell her. He had smiled that big doctor smile and said young ladies like me bring ourselves to psych emerge all the time. We just need to get grounded again, have a good night’s sleep. Swallow some tranquillizers.

Before I can assemble my thoughts, the psychiatrist exits, is replaced by a nurse. “Robyn, I need you to remove your purse and jacket.”

“Excuse me?” I rise from my chair, trying to quell the adrenaline trembling through the sedatives. “I have a job interview to go to. The doctor said I could leave this morning and at this rate I’ll be late.”

She takes one step closer, her face drained of sympathy. “The easier you make this for us, the easier it will be for you.”

“What? No, I need to speak to that doctor. There’s been a misunderstanding.” Sure, things have been wobbly, messy, dark. I haven’t been coping—or rather I’m an expert coper, all I’ve been doing is coping, when can I stop?

The nurse sighs. “I know it’s scary, but you have to stay with us for a while.”

“No. I don’t. I brought myself here and I’m leaving now.” Oh god, I sound like the other crazies. She grabs my purse, and we play tug of war. Her expression is muted, like she’s done this circus act ad nauseum.

“You can’t leave. There’s nothing to be done about that now. Let go of your bag and jacket,” she says breathlessly between tugs, vexed I haven’t submitted. “If you don’t cooperate, I’ll have to call security and you really don’t want that.”

“What do you mean? Please. I don’t understand.”

“You can’t leave,” she says, and wins, wrenching my purse—my car keys, wallet, cellphone and inhaler, a pair of earrings, pens and scraps of paper—into her hands.

When they forced me into the backseat of the car with tinted windows and jostled us through the Anti-Atlas Mountains, I maintained calm. Focus. Poise. But in the police chief’s office, I realized my choices were an illusion. Walls pressed up against my chest, squeezed through my composure as his approach shifted from yelling to flirtation: “You have such beautiful eyes.”

“I’m leaving,” I whispered.

“You can’t leave,” said the boy who convinced me to report the crime. He had approached me with flowing blue and gold robes, his face kind and naive: “You don’t want it to happen to another girl, do you?”

“Tu ne peux pas partir,” said the police chief, grinning. “Come closer, come to me, and show me again how he tried to grab you.”

“I’m leaving,” I repeated, and opened the office door, surprised to find it unlocked. I walked past a dozen male officers and the man excused of attempted rape because he offered me lunch. They had brought him into the station, without handcuffs, and sat him in front of me. As I attempted to report what he had done, I faced a dozen leering men.

“Maybe you should fight him again,” one of them said, enjoying this.

“Maybe you should tell him to respect women,” I retorted.

I expected someone to grab me and drag me back into the station, but I kept walking, head held high.

If I must, I’ll fight like I’ve fought before: “Qui est ta mère,” I yelled at him again and again amidst the parched valley. The unexpected words came from some intuitive, primordial place. Alone under the white sun, I could tell my primal roar, surging with a force unknown until now—Qui est ta mère, who is your mother—loosened his grip, just enough.

I rip my belongings back into my hands as the nurse staggers backwards, surprised by my strength.

I’m able to open the door and stride through reception. There’s yelling behind me; I don’t look back. Ahead, two security guards glance up, but my professional attire protects me from being deemed the cause of the commotion. I push open the doors and enter a maze of hallways just in time, slowing my gait to avoid suspicion. Was something on the loudspeaker? Code blue? Red? Orange? Down one hallway then the next, I clip past nurses wheeling patients, just a normal woman in a normal hurry to catch up with her busy schedule.

I don’t know how the system works: if I flee will they send cops to my house? Do I become a fugitive? Maybe I should turn myself in. What the hell is happening? I’ve committed no crime.

Daylight hits me. I stride towards my car. Almost there. Don’t. Run.

In my peripherals, two security guards analyze me from their van, but I’m not the AWOL girl in pajamas they envision, so they keep driving.

Footsteps approach from behind.

“What’s going on, Robyn?” says a stocky guard, maneuvering himself alongside me. “We’re told you ran from the hospital. That doesn’t seem like a very good idea, does it?” Another guard flanks my other side.

“I’m just going home,” I say, remaining steady like I did in the police station.

“Well unfortunately, we can’t let you do that. You can’t leave.”

I take a breath and keep walking.

“If you come with us now, we won’t have to hurt you.”

A male psych nurse with a horse-like face and bony arms shoves pajamas into my hands. Stage one of prepping for the role of mental patient: bid farewell to civilian clothes.

Inside the bathroom I stall for time, terrified and unwilling to surrender my dignity. No one has told me my rights.

Finally, I emerge in the baggy, dried-mustard–hued pajamas and surrender my emerald armour, my wardrobe of the sane, ensuring my bra is buried between my pants and blouse.

He rifles through the pile and smirks. “I need your underwear too.”

“That’s right,” he says. “You’re not above the rules. This is what happens when you misbehave.”

I shut the bathroom door as a sob escapes my lips. I remove my underwear and fold them up, hands and legs shaking, trying to maintain dignity before facing him. Having nailed the crazy girl audition, I was now stuck playing the part.

“Mental illness is a first world problem,” our city guide replies as we weave through rust-coloured Newari pagodas to visit Kumari, the Living Goddess, when my lungs are clear and my questions endless.

Of course, mental illness exists here too, and I’ve heard of families who lock their mad relatives away from the world, hiding them from public sight. But it’s also true there are different words for suffering here, and different cures.

After the hospital, our guide Kalsang generously insists I convalesce in Kathmandu with his family. Every morning at six a.m., his wife Dhriti invites me upstairs to join the ladies of the neighbourhood in following the merciless commands of their toned Pilates instructor. The women are wrapped in vibrant saris except the young instructor who sports lipstick and sweatpants and demands endless reps: be strong, don’t be weak! We shriek with laughter as we hop squat across the room like rabbits. The women giggle at my meager sit-ups, calling me “Luri,” skinny girl.

With her nephew washing and chopping, Dhriti cooks me three hefty meals a day to plump up the gaunt skin on my bones. Shooing me away from the kitchen, they prepare dahl baht with chicken curry, fiddleheads with masala paste, aloor dum with toasted coriander and hemp seeds, pickled soybeans and achar, pampadams, and steaming mugs of chai with sukumel, luwang, and a touch of black pepper. One evening we eat smoked tiger from Dhriti’s village: not normally permitted, but the animal crept out of the jungle to hunt cattle. The sinewy meat has been softened in a sweet and spicy curry.

Dhriti’s family sometimes rely on jhākris, shamans, when one of them falls ill. Doctors can be expensive and untethered from the local culture and worldview, so modern medical treatment is sought only under certain circumstances. To find the cause of illness, jhākris enter an altered state of consciousness, using trance and ritual to journey into unseen realms and communicate with spirits and deities. There they can find solutions and call back the missing pieces of a person’s soul to restore them to wholeness.

Due to globalization and the infiltration of biomedicine, missionaries, and non-profits, these cures are increasingly seen as backwards and superstitious, an obstacle to “mental health care for all.”

“No, we don’t have mental illness here,” echoes Kalsang to my raised brow, and perhaps they are right to preserve their own illness narratives rather than consume colonial conjurations of questionable chemical imbalances. At home, our cultural healers with prescription pads consult the DSM oracle and haunt us with projections of chronicity: is she complex PTSD or a disordered personality, mania or a psychotic fantasy?

But doctor, isn’t our deepest suffering a kind of fragmentation of the soul?

There are parts of me still missing and I want them back. Maybe there’s truth to the cruelty people surely whisper: she’s “not all there.” But if I’m not all here, where else am I? How do I bring all of me home?

“What if it happens again?” I ask Yael, weeks of frantic insomnia thinning my voice. She sits across from me with that cheeky gaze, her rattles and smudge sticks grounded in no-bullshit bluntness. On weekends we journey to unseen realms, listening to a myriad of voices that could get us locked up in one reality and praised for strong intuition, healing and visionary potential in another.

In Peru, I learned about the Q’eros, Indigenous Peruvians who managed to preserve their culture and spiritual practices after Spanish colonization. They communicate directly with the apus (mountain spirits) and believe we’re at a time of great cultural transformation and heightened consciousness, depending on our collective choices. I find it comforting that in some consensus realities, hearing voices is a gift rather than a cerebral malfunction.

“What do you mean?” she asks.

“The psychosis. The hospitalizations.” Being helpless, at the mercy of those in power.

“But why would it happen again?” she answers with impish impatience. “You already know it needed to happen. You were shoving down your authentic self for too long, ignoring the wisdom of your body. These two ways of being couldn’t coexist in conflict forever. Eventually you had to break. You broke wide open. And now?”

Healing never happens in sterile white panopticons: “care” without consent. It happened after release, half-naked on a bustling downtown street as men and women, strangers, wrote words of healing on my body: “You’re a goddess,” “It’s not your fault,” (a panacea to “you shouldn’t have gone traveling alone,” and all the rest), in blue, green, purple and yellow paint. It happened as I trained in self-defence—upper cut, right hook, rear-naked choke—and felt safe in my body again. It happened as I cried and raged into rivers, took flight and traveled to distant lands again, realized I wasn’t the sick one. As my soul pieces returned to me, I stopped convulsing at night, settled into sleep, into dreams that lost their terror and grew in vibrance.

During the unraveling, I obsessed about escaping into the wild to be healed by the dirt and muck and mulch of the earth, where I would absorb the powers of the universe. A doctor at the hospital said this was a common delusion. “Tsk, tsk, tsk,” he scolded. “Nice young women shouldn’t be thinking those things.”

Why do so many mad people seek answers in the forest, away from the metallic hum of cities?

Once a plodding stability was achieved, I wanted, needed to see what would happen if I did it, completed the quest. I was terrified to camp in the woods, something I had done since childhood, because this might be delusion speaking; I might come undone. My boyfriend kissed me on the forehead and said, “No, I don’t think you’re going crazy again. But if you are, we’ll get through it.”

I took a week off work and went alone.

Naked I swam in waterfalls, I built fires and listened to the voices many of us hear (did I remember to turn the stove off?) and a few extra (a wrinkled crone chuckling at my fears and telling me, lovingly: you’re not so special, not the only one to lose your mind and find something more important).

On the rocky beach, I met a woman named Sarah gathering driftwood. As a storm approached, she led me into the sheltered woods, unfolded her single burner stove, and cooked us coconut soup that tasted like sunshine. “You might think this is weird,” she said, “but sometimes I hear messages from the earth.”

“Oh yeah?” I said nonchalantly. “Do you hear a message now?”

“Yes,” she smiled, “this one’s for you.”

And with her answer (and a second helping of golden soup), another piece of me, perhaps still locked in the hospital, soared through unseen realms and returned home.

The head psychiatrist sees me every morning. He’s a short, balding man whose mouth curls down in constant distaste. I bite the inside of my cheeks to keep from asking my usual: “When can I go home?” Even though my brain is sludgy from the cocktail of meds, it knows pleading for release will only extend my stay. In British Columbia, people committed under the Mental Health Act are deemed incapable of consent. While under the “protection” of the state, staff can force any treatment, medication and injection into us, no matter the brutal side effects. Not even our family members have a say in what happens. Electro-convulsive therapy can be ordered, if not with informed consent, then by a “substituted decision maker.” For those of us who reject our meds after the hospital, we can be forced to get monthly antipsychotic injections into our ass, indefinitely. We can be involuntarily committed for months at a time based on the psychiatrists’ whims. No fair trial if you’ve committed the crime of instability.

“I’m glad you’re starting to understand the consequences of your actions,” he tells me, peering up from his notes. “You seem to be taking responsibility for what happened.”

I nod eagerly, masking my confusion. Am I taking responsibility for what he keeps insisting is a biological illness? Or was it running away from this place I’m supposed to be sorry for? Either way, I must appear submissive if I’m going to get out.

There are consequences for causing disruption. We’re written up as “non-compliant” if we ask questions about our treatment or the disturbing med effects, so we sit quietly in our own orbits as gravity sinks its grip.

Karen and Sally are pretty blondes with big, bloated bodies: a common side effect of antipsychotics that alter metabolisms and can cause diabetes. Karen stares at the quadrants of food on her tray: chocolate pudding, some beige vitamin drink, milk, and the microwaved dish of the day. “What should I eat first?” Karen asks, her voice monotone and hushed. “What do I do now?” she asks no one in particular. When nobody responds she repeats, “What do I do now?” There isn’t much to do inside besides consider our failed life choices, so I don’t know what to tell her.

Desperate for stimulation, I ask staff, “Can I do something? Help with…the cleaning?” They instruct me to focus on my recovery, which consists of staring at white walls. There is no therapy here, or music, or laughter.

One of the well-meaning nurses lectures me about the importance of staying off hard drugs. “Crystal meth destroys brain cells,” she says with pity in her eyes.

“I’ve never done meth,” I say for the third time.

She smiles knowingly. “And sleep is so important. Meth keeps people awake and makes them think they don’t need to sleep.”

I don’t bother mentioning I tried everything—acupuncture, therapy, yoga, meditation, prescribed medication, chakra cleanses, vitamins, sex, wine, melatonin, binaural beats, and counting sheep—and still, still I can’t sleep I can’t sleep I can’t sleep.

“Just keep taking your oxazepam,” she continues. “Even if you take it for a year, it’s better than using meth.”

Benzodiazepines exacerbate insomnia and suicidal thoughts, not to mention being dangerously addictive. But when you’re in the loony bin, everything you say is considered crazy. It’s better to smile and suppress a scream: Okay. I’ll stop taking the meth I never took.

Sally cries out that she’s being molested, and a nurse rushes over to make her swallow meds. I wonder how they know she’s just hallucinating. What if it’s a memory that needs to emerge and be witnessed?

Karen addresses the room again, “What do I do now?”

“Karen,” I croak, like rousing a rusted machine. “Karen. Tell me about your favourite memory.”

Karen’s sluggish gaze finds mine. She looks so innocent, a child in a grown woman’s body. “My favourite memory?”

“Yeah.” My brain feels squeezed by metallic bands, but I fight to hold focus.

“Oh.” She’s quiet for a moment, and then her entire face lights up. “Being a mom.” She’s so radiant I can’t help but smile. “Being a mom and looking after my kids.”

Sally and Zach look over. The nurse leaves and I turn to Sally, who is dozy and silent from the tranqs.

“And you? What about your favourite memory? Or a time when you felt most in control?”

“Going camping with my family in the summertime. When I was young. I saw a big bald eagle.” Her face lights up too, just for a moment.

We turn to Zach who is thrilled we’re exhibiting signs of life: he buzzes a mile a minute and doesn’t fit into such a contained space; forcing him here is like wrestling shrouds over a burning sun. “Driving the Kia Optima,” he says, “the most fun car I’ve ever driven. Yeah. I enjoyed the Kia the most. Felt in control, because…I was controlling exactly where I was going. It was so nice because I usually take the bus. The Kia smelt like fresh leather. You know, that fresh, new smell.”

I write it all down with an orange Crayola. That’s all the positivity I can muster before slinking back into morbid thoughts. But when I’m allowed pens, I draw portraits of my fellow patients. On Sally’s I write, “You have a strong and powerful voice.” When I give her the drawing, she gasps and wraps me into a big hug.

Every day, we had to fill out suicide checklists declaring how likely we were to off ourselves. Not one staff member, though, ever asked what happened to us to make us court death as a solution to our pain.

Even if they did ask us how we were doing—I mean really ask, not just shove checklists into our hands—it wasn’t safe to tell them the truth.

I couldn’t tell them, for example, that I saw my spirit leave my body. I tried to call it back to me, but why should it have listened? My body had become inhospitable terrain. It had been threatened and assaulted, swallowed my rage and self-hate—misdirected arrows—and when its owner went looking for help, it was imprisoned and sedated into submission. So when I looked into the mirror a husk stared back, and when I pleaded with sleep to come for me, wrapped in my boyfriend’s arms, pretending to be dreaming, I saw a golden ball of light darting through the stratosphere: you can’t catch me! I’m not going back there, no way, José. I’m flying far, far away from you.

I lie awake for hours. My shirt and sports bra are drenched in stale sweat, but at least these clothes are my own. Light from the hallway seeps underneath the door. A familiar tightness clenches over my heart, joins the groaning ache in my lungs: This place is not safe, I’m a fugitive on the brink of being discovered. Somehow, they will unearth my medical records. They will send me to a bad place with locked doors and no gardens.

I remind myself that the staff here, now, have been kind, and security’s job is to keep others out, not me locked up inside, and despite the fear and the insomnia I’m not about to lose my mind, and finally I let my guard down enough for sleep to pull me under.

In the dream I fall. Flickers of candlelight illuminate faces known and unknown.

I wake, my breath a shallow whisper. My lips are numb and tingling from lack of oxygen. Fear shoots through my body, but before I can call for help, darkness.

I jolt awake again as I roll to the floor. Disoriented, I scramble to my knees, untangle myself from the IV and return to bed, but there’s already somebody underneath the sheets. My own body lies unconscious beneath me.

I’m pulled through the doorway, down the hall, up out of the hospital, then higher still, through grey clouds with deep purple underbellies. I’m dying but this feels familiar, serene. When I look down towards my body, cords of golden light, like glowing tentacles of a jellyfish, sway between me and the ground, incomplete possibilities.

Death is right beside me, a gentle current…

I claw my way back down to my body. I awake breathless and scramble to inhale lungfuls of salbutamol, forcing breath down into my diaphragm. I’m terrified to fall back asleep, because what the actual fuck just happened, but I’m here now. I’m not going anywhere.

The next morning, the doctor tells me my white blood cell count has decreased from 23000 to 17000, a good sign. A healthy person’s count is around 7000, so I have to stay a few more days. “How many more days, do you think?” I ask tentatively, preparing for his suspicion.

“Probably just two or three more.” He smiles. “You’re strong and I believe you will recover.”

The warmth and assurance of his words ease my rigid shoulders. Where had those words been before? Instead of “recover” it was “manage,” like I had to become my own supervisor, ceaselessly on the lookout for self-deception and non-compliant behaviour.

“The nurse told me you had difficulties sleeping last night,” he says with concern.

My stomach flips. “Oh it’s fine, I just have a hard time sleeping in new places— ”

“Do you want us to wait until morning to check your vitals? So you can get a better sleep?”

“Oh,” I say, amazed. A choice? “Okay. Thank you.”

For lunch, I order tandoori chicken with butter naan and a fresh banana smoothie. The tandoori comes nestled on a heaping pile of steamed vegetables grown in the garden outside my window. The garden is almost as big as the hospital and teems with green leafy plants. A gecko appears from behind the drapes and crawls across the wall.

I set down my fork, eyes filling with tears. There was no hesitation. Every part of my being chose life. It wasn’t the first time my spirit left my body, but this time all of me wanted to be here.

Maybe the sickness, like the madness, was teaching me, the message Sarah whispered from the forest: You need to learn to be kinder to yourself. Allow myself to be weak, to be injured, instead of bullying myself forwards: one step, two step, I got away, didn’t I? But not all of me: trapped in that scorched valley while the rest of me fled to Agadir.

If I want, I can haul my IV drip to the courtyard and sit in the sun, fragile pink, red, and white flowers sharing their strength and their fragrance. Or I can hang out with my mascot, the giant spider who lives in the bathroom.

What would the ward have been like if there were gardens and open gates? If our aching spirits had been given as much care and consideration as the chemicals in our brains? If the doctors told us we would recover, rather than declaring the many ways we were broken?

Because we were never broken. We just needed good reasons to come back down to earth.

I raise my face up to the sunlight, to the whole, expansive sky.